- Wake Up With BroadwayWorld June 17, 2025

- Video: Baayork Lee & Donna McKechnie Are Carrying the A CHORUS LINE Torch 50 Years Later

- Inside Rachel Zegler's Outdoor EVITA Performance: How to See It, New Videos & More

Latest News

Trending Stories

Recommended for You

Benny Andersson & Björn Ulvaeus Are Making a Broadway Comeback

Later in 2025 both Chess and Mamma Mia! will be revived on Broadway.

The Business Behind Broadway: When and Why Shows Open or Close

Is there a time of year that Broadway shows typically open and close?

Video: Watch Highlights of the Broadway-Bound Cast of MAMMA MIA!

Mamma Mia! will return to the Winter Garden Theatre in 50 days.

Photos: The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event.

Ticket Central

Hot Photos this week

Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more!

Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

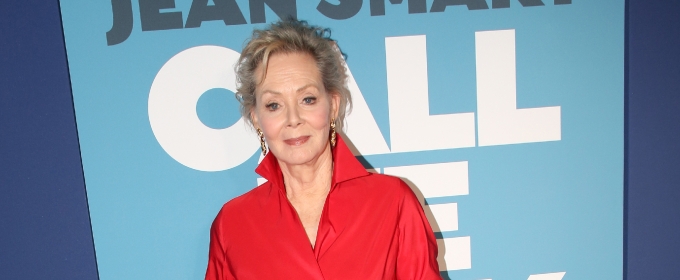

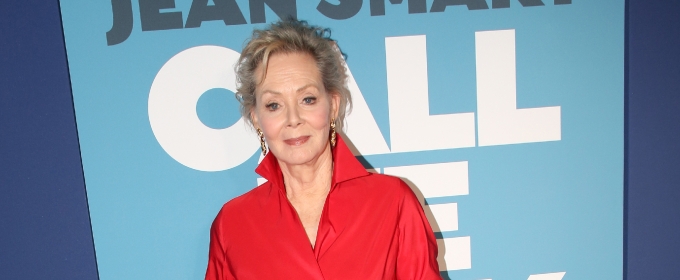

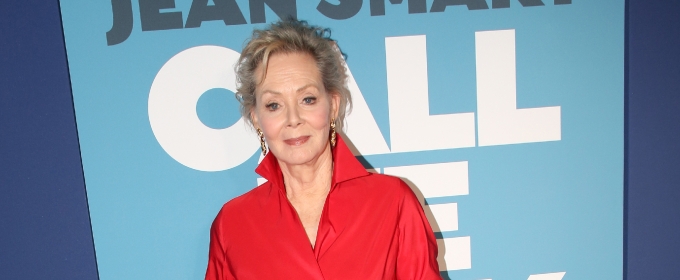

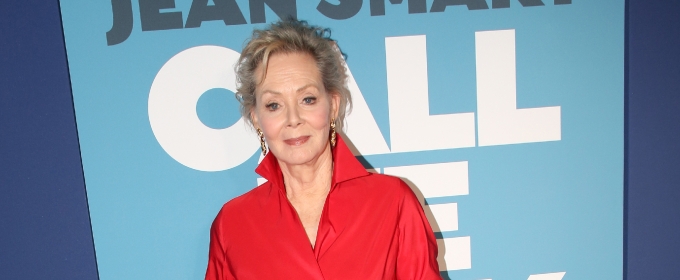

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more! Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54.

Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54. BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda.

BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda. The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event.

The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

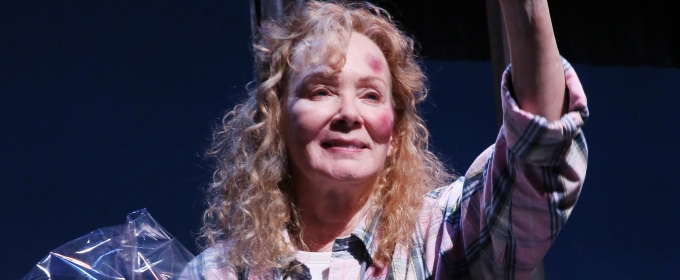

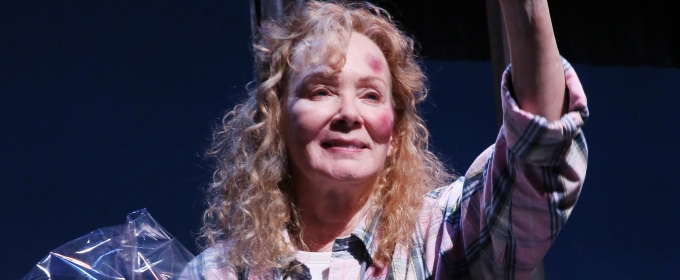

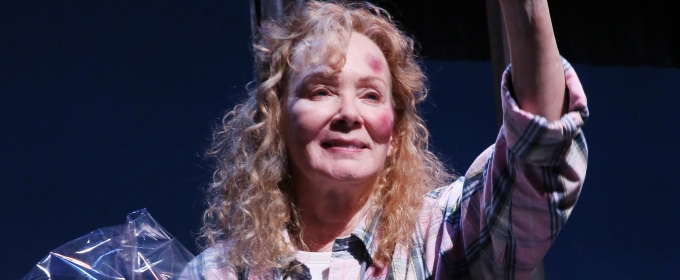

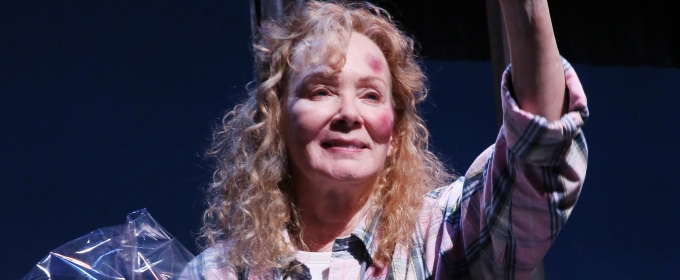

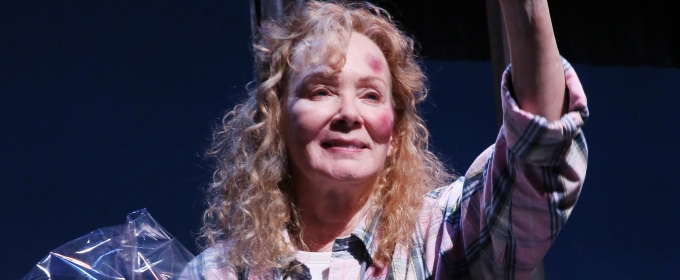

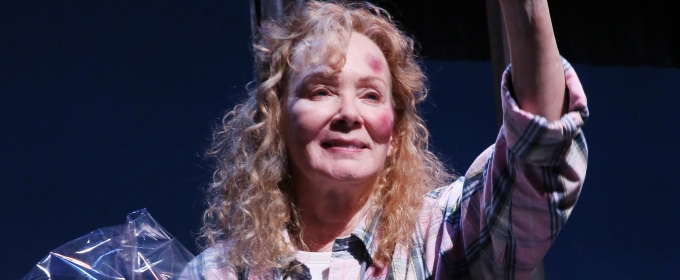

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

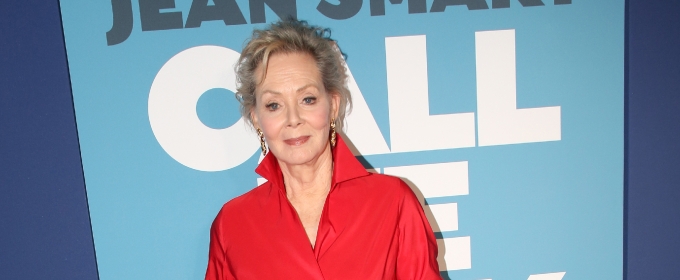

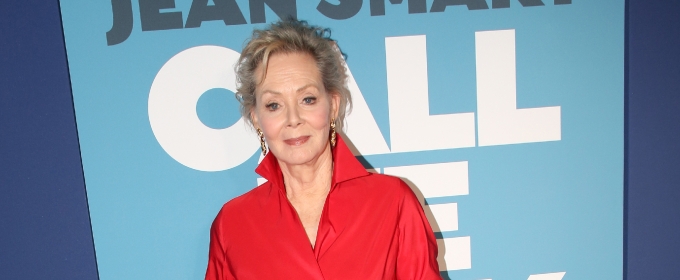

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54. Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54.

Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54. BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda.

BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda. The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event.

The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54. First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4.

First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4. BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda.

BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda. The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event.

The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54. First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4.

First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4. James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy.

James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy. The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event.

The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54. First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4.

First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4. James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy.

James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

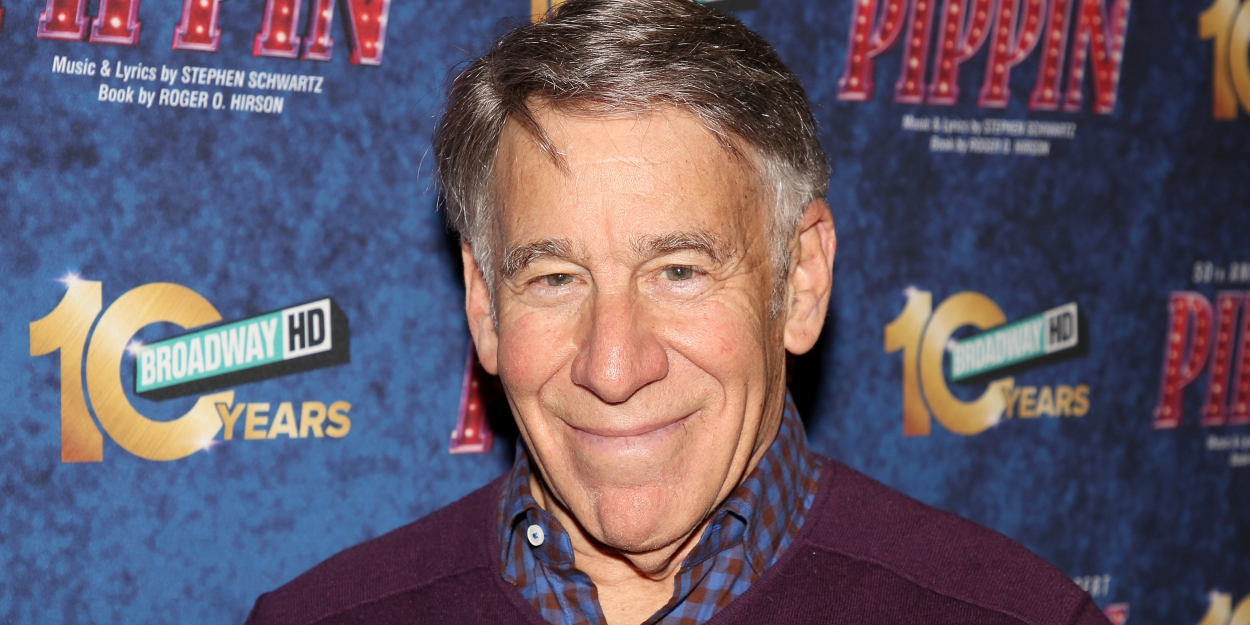

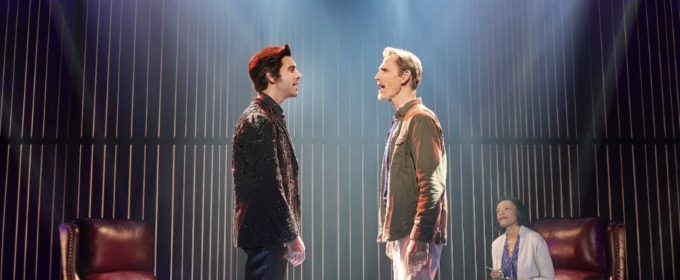

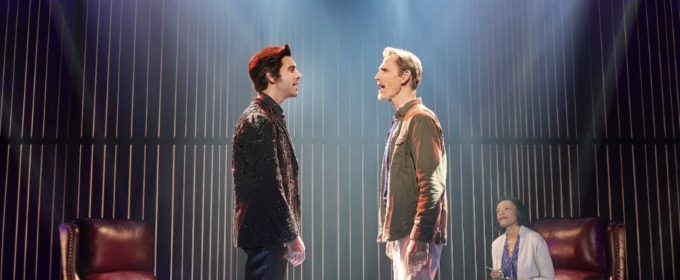

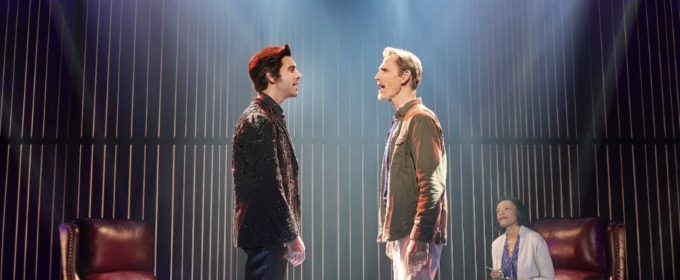

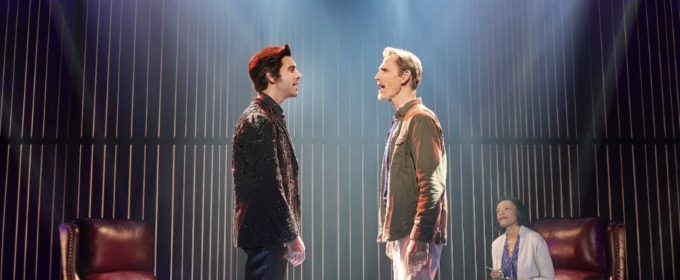

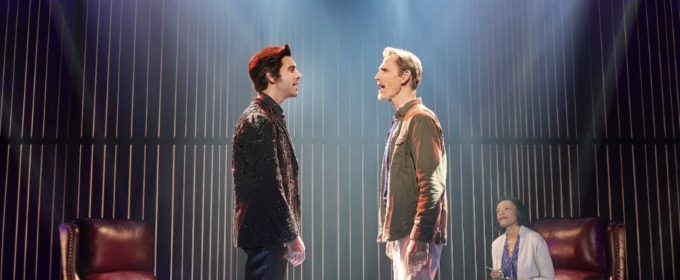

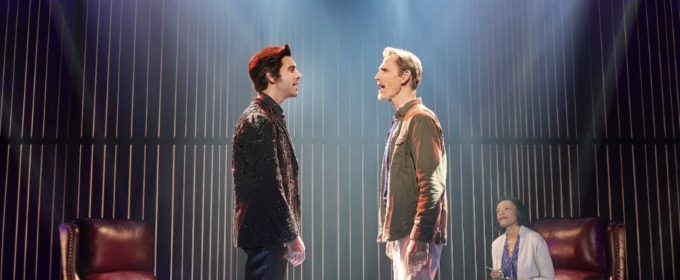

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy. Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing

Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54. First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4.

First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4. James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy.

James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy. Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing

Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages

HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Hit the Red Carpet on Opening Night

Performances run through August 17, 2025 at Studio 54. First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4.

First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4. James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy.

James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy. Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing

Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages

HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29

Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29 First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4.

First Look at Rachel Zegler in EVITA in London

A vinyl, featuring Zegler performing "Don’t Cry For Me Argentina", will be released on July 4. James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy.

James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy. Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing

Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages

HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29

Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29 Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29.

Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29. James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy.

James Taylor, Carrie Coon, and Tracy Letts Visit DEAD OUTLAW

Coon and Letts even got into the infamous coffin from the production to try their best at embodying Elmer McCurdy. Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing

Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages

HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29

Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29 Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29.

Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29. MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15.

MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15. Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing

Review: A BEAUTIFUL NOISE: THE NEIL DIAMOND MUSICAL at Golden Gate Theatre

More Than a Juke-Box Musical, a Journey of Healing HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages

HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29

Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29 Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29.

Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29. MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15.

MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

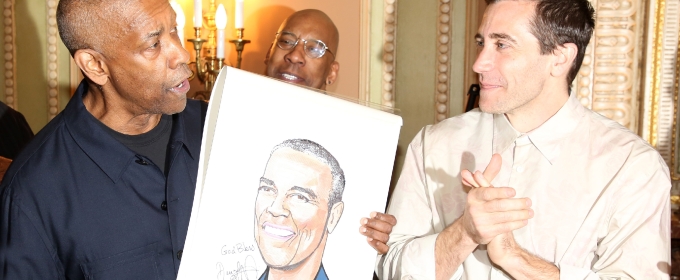

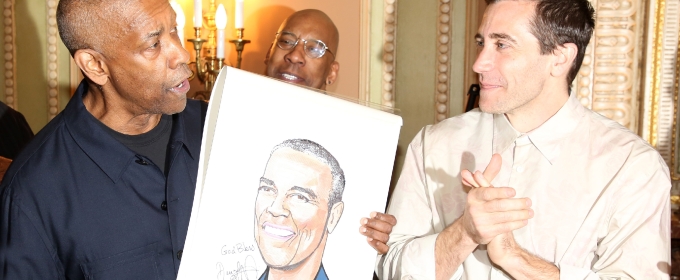

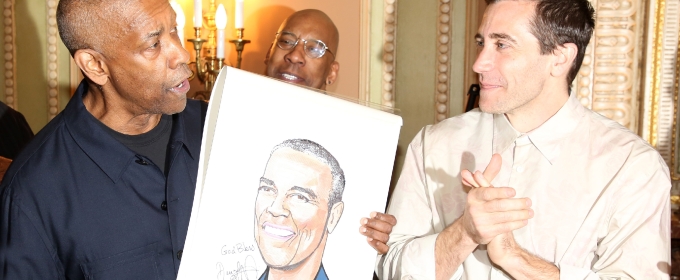

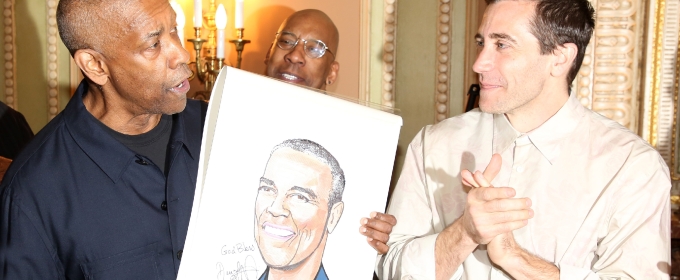

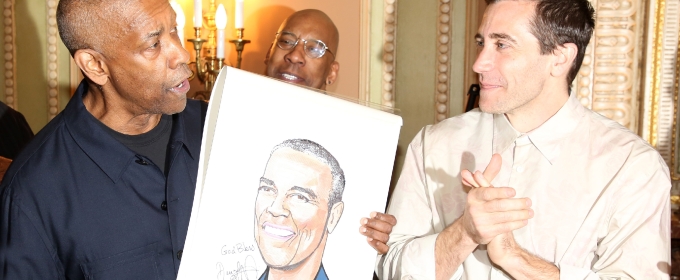

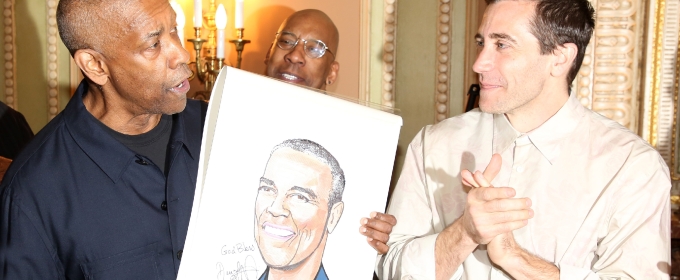

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15. OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre.

OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre. HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages

HEATHERS THE MUSICAL Cast Meets the Press

The show's Off-Broadway return will start performances on June 22, 2025 and will play a limited engagement through September 28, 2025 at New World Stages Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29

Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29 Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29.

Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29. MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15.

MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15. OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre.

OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

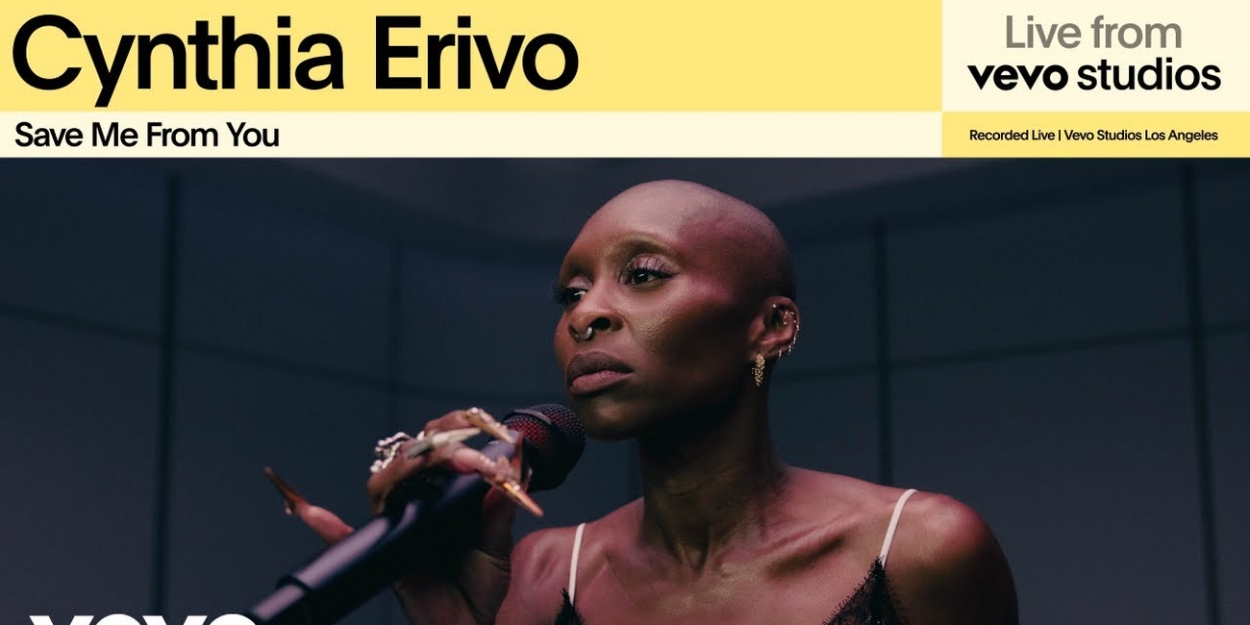

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre. Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo.

Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo. Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29

Review: THIS HOUSE at Opera Theatre Of St. Louis

World premiere at OTSL runs through June 29 Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29.

Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29. MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15.

MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15. OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre.

OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre. Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo.

Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo. First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts.

First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts. Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29.

Sierra Boggess, Taylor Mac and More in PROSPEROUS FOOLS

The production will run through June 29. MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15.

MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15. OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre.

OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre. Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo.

Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo. First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts.

First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts. COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025.

COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025. MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15.

MY SON'S A QUEER (BUT WHAT CAN YOU DO?) At New York City Center

The hit show is playing a five night limited engagement at New York City Center from June 12 until June 15. OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre.

OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre. Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo.

Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo. First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts.

First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts. COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025.

COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025. Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater.

Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater. OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre.

OTHELLO Star Denzel Washington Celebrates Sardi's Portrait Reveal

Othello will conclude its Broadway run this Sunday at the Barrymore Theatre. Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo.

Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo. First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts.

First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts. COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025.

COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025. Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater.

Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater. Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27

Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27 Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo.

Inside the 4th Annual Black Women on Broadway Awards

The event honored LaTanya Richardson Jackson, LaChanze, Khaila Wilcoxon and Cynthia Erivo. First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts.

First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts. COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025.

COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025. Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater.

Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater. Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27

Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27 DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre.

DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre. First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts.

First Look Disney's FROZEN At La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts

Frozen runs through June 29 at La Mirada Theatre for the Performing Arts. COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025.

COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025. Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater.

Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater. Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27

Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27 DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre.

DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre. BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre.

BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre. COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025.

COME BACK TO THE 5 & DIME, JIMMY DEAN, JIMMY DEAN at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley

Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean: A New Musical will perform June 18 – July 13, 2025. Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater.

Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater. Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27

Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27 DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre.

DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre. BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre.

BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre. Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony.

Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony. Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater.

Cinnabar Theater Concludes 52nd Season with BRIGHT STAR at Sonoma State

The show will run from June 13 through 29, 2025 at the Warren Theater. Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27

Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27 DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre.

DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre. BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre.

BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre. Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony.

Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony. Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer!

Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer! Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27

Review: DON PASQUALE at Opera Theatre of St. Louis

Plays at Opera Theatre of St. Louis through June 27 DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre.

DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre. BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre.

BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre. Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony.

Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony. Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer!

Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer! SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row."

SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row." DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre.

DILARIA Unveils Character Posters and Rehearsal Shots

Performances begin on Thursday, June 13, 2025, with an opening night set for June 18, 2025, at the DR2 Theatre. BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre.

BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre. Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony.

Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony. Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer!

Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer! SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row."

SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row." ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025

ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025 BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre.

BOOP! THE MUSICAL Stars Jasmine Amy Rogers Gets Her Very Own Sardi's Portrait

Boop! The Musical continues its run at the Broadhurst Theatre. Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony.

Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony. Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer!

Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer! SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row."

SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row." ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025

ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025 Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined.

Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined. Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony.

Inside Opening Night of ANGRY ALAN, Starring John Krasinski

Studio Seaview held its official ribbon cutting ceremony. Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer!

Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer! SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row."

SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row." ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025

ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025 Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined.

Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined. SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization.

SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization. Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer!

Theater on the Go: A Day in the Life with the Public Theater's Mobile Unit

Mayelah Barrera is taking us inside a day with the cast of Much Ado About Nothing, coming to all five boroughs this summer! SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row."

SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row." ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025

ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025 Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined.

Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined. SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization.

SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization. THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley.

THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley. SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row."

SMASH Cast Celebrates Marilyn Monroe's 99th Birthday

The cast unveiled the new street sign for West 45th Street, which was temporarily renamed “Marilyn Mon-Row." ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025

ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025 Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined.

Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined. SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization.

SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization. THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley.

THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley. Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more!

Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more! ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025

ROCKY at Tacoma Little Theatre

Rocky will run Friday, June 6, through Sunday, June 29, 2025 Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined.

Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined. SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization.

SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization. THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley.

THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley. Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more!

Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more! THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29.

THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29. Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined.

Review: LONG DAY'S JOURNEY INTO NIGHT, Golden Goose Theatre

Eugene O'Neill's heartbreaking play reimagined. SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization.

SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization. THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley.

THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley. Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more!

Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more! THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29.

THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29. Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more!

Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more! SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization.

SLAY THIS WAY II Raising Money for The Felix Fund

Slay This Way II lit up The Cutting Room on Tuesday, June 10, 2025, for its second annual Pride Month celebration and benefit for The Felix Organization. THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley.

THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley. Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more!

Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more! THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29.

THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29. Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more!

Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more! Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54.

Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54. THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley.

THE UNTITLED UNAUTHORIZED HUNTER S. THOMPSON MUSICAL At Signature Theatre

Now running through July 13, the production is directed by Tony Award winer Christopher Ashley. Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more!

Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more! THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29.

THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29. Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more!

Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more! Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54.

Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54. BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda.

BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda. Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more!

Kieran Culkin Receives Sardi's Portrait

See photos of Glengarry Glen Ross cast members and more! THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29.

THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29. Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more!

Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more! Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54.

Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54. BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda.

BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda. The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event.

The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event. THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29.

THE ANGEL NEXT DOOR at International City Theatre

Performances continue through June 29. Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more!

Backstage with the 2025 Tony Awards Winners

Winners included Maybe Happy Ending, Sunset Blvd. ad more! Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54.

Emmy-Winner Jean Smart Stars In CALL ME IZZY On Broadway

The 12-week limited engagement is now playing at Studio 54. BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda.

BUENA VISTA SOCIAL CLUB Celebrates Its Tony Wins

Among the evening’s notable guests was Lin-Manuel Miranda. The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event.

The Public Theater Celebrates the Newly Renovated Delacorte Theater at 2025 Gala

Leslie Odom Jr. and Renée Elise Goldsberry performed at the special event. CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54.

CALL ME IZZY Star Jean Smart Takes Her Opening Night Curtain Call

CALL ME IZZY is running through August 17 at Studio 54.Industry

Get Broadway's #1 Newsletter

West End

New York City

PRIDE PLAYS 2025 Announces Casting For New York Festival

Pride Plays 2025 in New York will take place on Monday June 23, 2025, at The Robert W. Wilson MCC Theater Space.

Pride Plays 2025 in New York will take place on Monday June 23, 2025, at The Robert W. Wilson MCC Theater Space.

United States

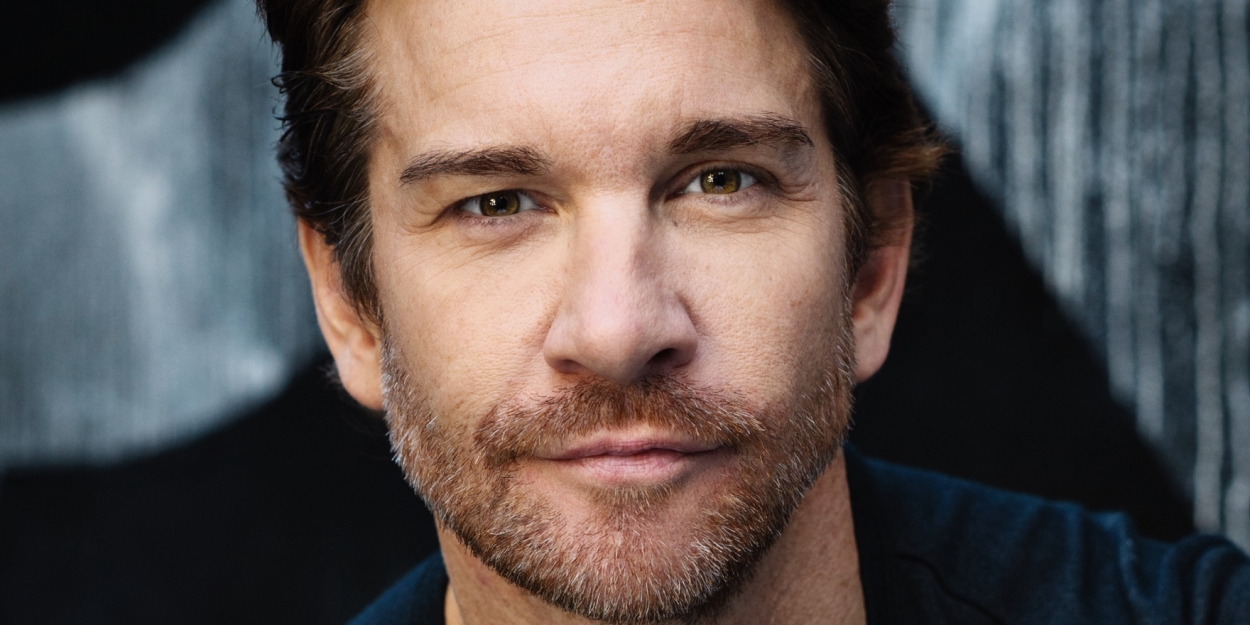

Interview: Trevor James of PARADE at Ahmanson Theatre

Performances run through July 12.

Performances run through July 12.

International

Kashkol Collective’s Bazm-e-Aam Set For This Month

Held at the India International Centre,Bazm-e-Aam brought together an enthusiastic gathering of Delhiwalas.

Held at the India International Centre,Bazm-e-Aam brought together an enthusiastic gathering of Delhiwalas.